ക്രെഡിറ്റിൽ സ്ത്രീ-പുരുഷ വിവേചനം; ഐ.എഫ്.എഫ്.കെ ഓപ്പൺ ഫോറത്തിൽ വിമർശനം

തിരുവനന്തപുരം: ഐ.എഫ്.എഫ്.കെയുടെ ഭാഗമായി ഞായറാഴ്ച നടന്ന ഇന്ത്യൻ സിനിമയിലെ പുരുഷാധിപത്യം: അധികാരം, ലിംഗം, രാഷ്ട്രീയം എന്ന ഓപ്പൺ ഫോറം, സി

Anuparna Roy’s 'Songs of Forgotten Trees' Draws Applause Thiruvananthapuram: Anuparna Roy’s film ‘Songs of Forgotten Trees’ received an enthusiastic response from the audience on Day Two of IFFK, at Kalabhavan Theatre on Saturday. The film, which won the Orizzonti Award for Best Director at the Venice

ചർച്ചചെയ്ത് ുവനന്തപുരം: അന്താരാഷ്ട്ര ചലച്ചിത്രമേളയുടെ 30-ാം പതിപ്പിലെ ആദ്യ ഓപ്പൺ ഫോറം, സിനിമാപ്രവർത്തകരും വിമർശകരും പ്രേക്ഷകരും തമ്മിൽ വിമർശനാത്മക സം

Mumbai: Tightening the screw on Rahul Bhatia-controlled IndiGo, aviation safety regulator DGCA has set up an eight-member oversight team, following the airline cancelling flights in large numbers due to crew shortage. According to an order issued by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) on Wednesday, the oversight team will

Thiruvananthapuram: The 30th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) is all set to celebrate the centenary of the legendary director Ritwik Ghatak with a special retrospective. The festival will screen four of his most notable films, presenting them in restored versions to a new generation of cinema lovers. Ghatak’s

തിരുവനന്തപുരം: ലോക സിനിമയുടെ സമകാലികവും ചരിത്രപരവുമായ കാഴ്ചകൾ കോർത്തിണക്കി മുപ്പതാമത് രാജ്യാന്തര ചലച്ചിത്രമേള ഡിസംബർ 12 മുതൽ 19 വരെ തലസ്

തിരുവനന്തപുരം: ലോക സിനിമയുടെ സമകാലികവും ചരിത്രപരവുമായ കാഴ്ചകൾ കോർത്തിണക്കി മുപ്പതാമത് രാജ്യാന്തര ചലച്ചിത്രമേള ഡിസംബർ 12 മുതൽ 19 വരെ തലസ്

പനാജി: പബ്ബുകളിലും നൈറ്റ് ക്ലബ്ബുകളിലും റസ്റ്റോറന്റുകളിലും പടക്കം, ഇലക്ട്രോണിക് പടക്കം പൊട്ടിക്കുന്നതിനും ഗോവ സര്ക്കാര് നിരോധനം ഏര്പ്പെ

രാഷ്ട്രപതി ദ്രൗപതി മുർമു നാളെ മണിപ്പൂർ സന്ദർശിക്കും. രണ്ടുദിവസത്തെ സന്ദർശനത്തിനായാണ് രാഷ്ട്രപതി ഇംഫാലിൽ എത്തുന്നത്.ദ്രൗപതി മുർമുവിന്റെ

രാഹുൽ മാങ്കൂട്ടത്തിലിനെതിരായ രണ്ടാമത്തെ കേസില് മുൻകൂര് ജാമ്യം ലഭിച്ചതിനെതിരെ സര്ക്കാര് അപ്പീല് പോകും. ഉടൻ ഹൈക്കോടതിയെ സമീപി

A bilingual Malayalam, English Newspaper

ചലച്ചിത്ര പ്രവര്ത്തക ഭാഗ്യലക്ഷ്മി ഫെഫ്കയില് നിന്ന് രാജിവച്ചു. നടന് ദിലിപീനെ തിരിച്ചെടുക്കുന്നതില് പ്രതിഷേധിച്ചാണ് രാജി. ഇനി ഒരു

ദുബായ്: എമിറേറ്റിലെ ഹോട്ടലുകളില് ഡിജിറ്റല്, കോണ്ടാക്റ്റ്ലെസ് ചെക്ക് ഇന് സൗകര്യം നടപ്പാക്കുന്നതിന് അഗീകാരം. യുഎഇ ഉപപ്രധാനമന്ത്രിയു

മേജർ ലീഗ് സോക്കറിൽ ഈ സീസണിലെ മികച്ച താരമായി തെരഞ്ഞെടുക്കപ്പെട്ട് ലിയോണൽ മെസി. തുടർച്ചയായ രണ്ടാം സീസണിലാണ് മെസി പുരസ്കാരം സ്വന്

Thiruvananthapuram: The 30th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) will focus on an array of distinguished films from Latin America, a land close to the heart of Keralites. The curated package includes Laura Casabe’s ‘The Virgin of The Quarry Lake’, Cecilia Kang’s ‘Elder Son’, Luciana Piantanida’s ‘All

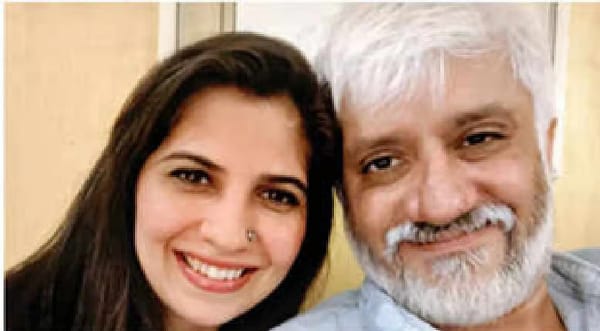

Udaipur: Bollywood filmmaker Vikram Bhatt and his wife, Shwetambari, were remanded to seven days' police custody by a local court in Udaipur on Tuesday in connection with an alleged fraud case exceeding Rs 30 crore. The couple, arrested from Mumbai on December 7, was brought to Udaipur by a

ന്യൂ ഡൽഹി: നിരവധി യാത്രക്കാരെ ബാധിച്ച വിമാന യാത്രാ പ്രതിസന്ധിക്ക് പിന്നാലെ ഇൻഡിഗോ റീഫണ്ടായി തിരിച്ചുനൽകിയത് വലിയ തുകയെന്ന് റിപ്

തിരുവനന്തപുരം: സ്ത്രീത്വത്തെ അപമാനിച്ചെന്ന് ആരോപിച്ച് പ്രമുഖ സംവിധായകനെതിരെ പരാതി നൽകി ചലച്ചിത്രപ്രവർത്തക. മുഖ്യമന്ത്രിക്ക് നേരിട്ടാ

Beijing: China on Monday reacted positively to Russian President Vladimir Putin's visit to India, framing the three countries as an important part of the Global South and said sound trilateral ties are conducive to regional and global peace and stability, besides their own national interests. “China, Russia and

Actor Dileep, an accused in the sensational Kerala actor rape case, can walk free as a trial court in Kochi has acquitted him of all the criminal charges levelled against him. Honey M. Varghese, the Ernakulam Principal Sessions Judge, on Monday (December 8, 2025) acquitted Mr. Dileep of the offences

നടിയെ ആക്രമിച്ച കേസിൽ നടൻ ദിലീപിനെ വെറുതെ വിട്ടു. ഗൂഢാലോചന തെളിഞ്ഞില്ലെന്ന് ചൂണ്ടിക്കാട്ടിയാണ് ദിലീപിനെ വെറുതെ വിട്

തിരുവനന്തപുരം: ബലാത്സംഗക്കേസില് പ്രതിയായ രാഹുല് മാങ്കൂട്ടത്തിലിനെതിരെ പരാതി നല്കിയ യുവതിയെ സമൂഹ മാധ്യമത്തിലൂടെ അപമാനിച്ച കേ

New Delhi: TV actress and Bigg Boss 4 contestant Saaraa Khan, who rose to fame with the show 'Sapna Babul Ka... Bidaai', remarried on December 5, 2025. The actress tied the knot with her long-time boyfriend Krrish Pathak, who is the son of Sunil Lahri, the actor who